Intellectual Ambition

I read an article six months ago that I still think about. It opposed a lot of what I promoted in my undergraduate work.

It changed my mind.

The article by Gena Gorlin is titled, “Intellectual Humility is a Cop-out.”

Most people are familiar with the idea of intellectual humility. (Either by name or by essence.) Given the complexity of reality and the diversity of experience, it is better to humbly reevaluate our own thinking than to arrogantly brandish it as irrefutable.

It’s great to have discussions with people who are intellectually humble. They work to understand your point of view. They aren’t brash or contentious. They aren’t (here’s a fun word) braggadocios.

People who are intellectually humble don’t care about being seen as correct or right.

However, there’s a problem. As Gorlin discusses, intellectual humility encourages an insufficient relationship with knowledge. If the most prevalent goal of intellectual humility is to recognize that you could be wrong, then you’ve accomplished the goal as soon as you admit you don’t know things. Congrats.

But so what?

Here’s Gorlin’s solution:

“To the extent that we want to live well and build things worth building, we need to be right, a lot, and we need to know that we are—so that we have the courage and discernment to act on the knowledge we do possess. This is at least as important as ‘knowing what we don’t know,’ and arguably more so, if our goal is not merely to avoid missteps but to boldly and actively live well.

The best thinkers—and thus the best builders—are not intellectually humble but intellectually ambitious. They respect the work that achieving real knowledge and earned certainty requires, and they embrace that work as the requisite to a life fully and consciously lived.”

A week or so ago, I was reflecting in my journal. Here’s what I wrote:

It feels pretentious and arrogant to claim rightness among diversity and options. And arrogance is emotionally distasteful in our society, thus there is social pressure to not claim a monopoly on truth.

Alan Noble, in his book Disruptive Witness, pulls from Charles Taylor’s work and speaks to these ideas from a historical lens.

“In some ways, Western society has turned this experience of tentative belief into a virtue, which is significant because with the collapse of a shared belief system we lost a shared stable of virtues to aspire to. Being open-minded, refusing to draw conclusions, the idea that diversity of belief is a good unto itself—these are all results of a fundamental shift in our basic beliefs about the world. Thus, we aspire to be noncommittal” (42).

In today’s world, being noncommittal is praised but not praiseworthy. It is an open-mindedness that is futile because someone who is noncommittal within diversity is adrift. Open-mindedness must be sustained by assurance in what we know and harmonized by determination to know more. Only then does real progress grow.

“There is mystery, and the way to address that mystery is with rigor. It’s with self-doubt, with intellectual modesty, where you don’t assume narratives that are really beyond your reach. But at the same time, you believe in a destination and a quest for meaning that’s totally beyond your reach. And you quest for it incrementally. That tightrope, I think, is where technology can improve. It’s where beauty can happen and where relationships can be real.”

Intellectual ambition solves the same problems as intellectual humility but pushes further. Achievement is not found in admitting ignorance but in working to discover truth.

Thankfully, one can (and should) ambitiously pursue truth without being prideful. Being right and being humble aren’t mutually exclusive. Gorlin writes:

“The most epistemically secure (i.e., self-trusting) individuals tend to be the least concerned about proving how much they know or how right they are. Their fundamental goal is not to reassure themselves of their basic epistemic efficacy (which is already a settled matter), but rather to solve the next problem, answer the next question, master the next challenge on the road to building what they want to build.

As a result, they are comfortable asking ‘stupid questions’ and constantly pushing themselves to new frontiers on which they are once again beginners; in other words, they are comfortable being ambitious. Thus they often appear ‘humbler,’ on surface, than the insecure blowhards who lack such genuine confidence.”

Good comes from commitment to truth. Saying “I don’t know” is easy. Knowing what’s true takes work.

Piano Music

I’m thinking of releasing a single next month…

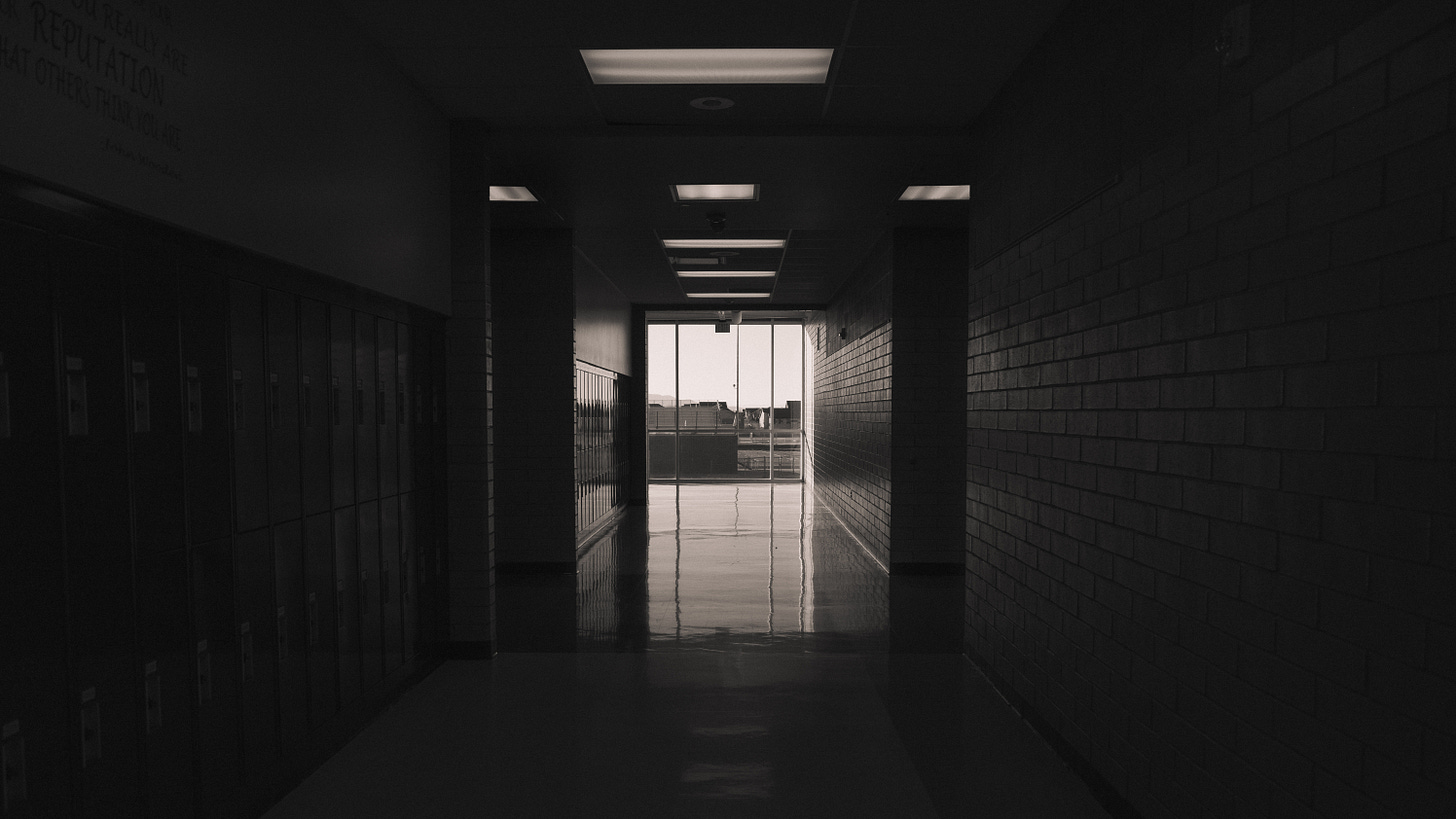

Photography

From School

“Nothing is good enough for Mr. Merrill.”

“I know I actually have to do good work for you. Some teachers don’t even look at stuff. Like this one teacher’s class? I can just type the same thing over and over so it looks like I’ve said a lot.”

“Mr. Merrill, what shoe size are you? Because I kinda like yours better and wanna trade.”

Me: “Hey check your email.”

Student: “Oh no.”

Me: “No don’t worry, it’s not bad.”

Student: “Did you Venmo me?”“Mr. Merrill you’re like my second father because I’m in here everyday.”

One of my students is prone to leave class or make excuses when she feels the work is too hard. She also has a sassy, defiant attitude. During class, she told me she had to use the bathroom. I told her she could go once she finished her writing. She said, “I have to go,” and then challenged me by saying if I didn’t let her, she would pee in the desk and make me clean it up.

Goodies

Sean Lew ☞ One of my favorite creatives/dancers/artists.

mymind ☞ Curate the internet with ease.

Untools ☞ Systems for better thinking.

Neal Agarwal ☞ A cool dude of the internet.

Cheers!

p.s. Merry Christmas and Happy New Years!

As I understand these words “ambition” and “humility” are not opposed to one another. The revolution that science brought (and still brings) is a) the humility that we don’t know how the world works and b) the ambition, and a method, to find out. Science progresses by creating hypotheses and then discarding and revising those hypotheses when something comes along that doesn’t quite fit. Science has to stay humble but it doesn’t shrug its shoulders and say that since it can only offer hypotheses, all hypotheses are equally valid. It is willing to say that a hypothesis was wrong (or incomplete) and keep seeking. Applying this to the social sciences and humanities is tricky. But that’s the challenge.

Very interesting observations about intellectual ambition. Thanks